As people “return to work” during the COVID-19 pandemic, employers should be ready to address a hidden issue: a meaning deficit.

Historically, every significant disruption of how we work inflicted profound distress flamed by existential crises and the search for meaningfulness.

At the height of the second Industrial Revolution, in 1897, sociologist David Émile Durkheim published an enduring analysis of suicide. Durkheim found a central cause of acute mental distress was the loss or change of work. Not working, he found, depleted people of purpose, of having a social function and a meaningful contribution.

In 1938, as The Great Depression relented, psychologists Philip Eisenberg and Paul Lazarsfeld discovered that unemployment resulted in a profound loss of identity characterized by brokenness and instability.

Even among a large group of workers who kept their jobs through the Great Recession between 2007 and 2009, Stanford University researchers found in-patient visits for mental health-related services were nearly four times higher than before the downturn. Feelings of uselessness and worthlessness were the most significant commonalities among those with mental health issues.

Uselessness and worthlessness are symptoms of meaninglessness, a pivotal contributor to feelings of despair.

Unlike these previous challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic is a crisis of both work and health insecurity intensified by the necessary but inhuman practices social distancing and isolation.

Even more than past economic disruptions, the pieces are in place for distress induced by our collective, unavoidable grasp for meaning in disorder.

And whether we like it or not, work dominates human life and is an inescapable context through which we make meaning of life itself.

Enabling meaningful work should be a priority for leaders and is a learnable skill.

The Looming Meaning Deficit

For the currently employed, the unemployed, and soon-to-be re-employed, emerging research shows the pandemic is prompting serious self-reflection.

New surveys show people who can work from home are spending more time contemplating the quality and meaning of their jobs and lives. Many are reflecting on their roles outside of work and trying to determine how to meet all of life’s demands.

A study from Alicia Sasser Modestino, an economics professor at Northeastern University, found that many, predominately women, have considered quitting their jobs to keep up with childcare and life demands. Yet, even 11% of men surveyed – said they, too, are considering leaving their current position.

For the 55 million essential workers who ensured everyone else could stay home, the sudden and short-lived public praise of their jobs reveals disparities between their value to society and the value their employers place on them.

The millions of people facing job and financial insecurity, unemployment, and those who’ll get hired back after months without work, are more at risk for feelings of meaninglessness, especially as many take less-than-ideal jobs to survive.

Add to these issues the widespread calls for social reform and racial justice that have led many to explore unexamined existential questions, and the ingredients are there for a looming meaning deficit.

Filling the Meaning Deficit Through Enabling Meaningful Work

Experiencing purpose, significance, and mattering in work isn’t a luxury, a generational preference, or a nice-to-have. For centuries, psychologists, philosophers, and now neuroscientists find that meaningfulness is a fundamental human need.

My and others’ research finds that meaningful work is desired and accessible in nearly any job or occupation, including work people take initially to earn a paycheck.

While it’s tempting to argue, especially in an economic recovery, that people just need income to survive, it’s essential to acknowledge that human beings are simultaneously what they basically need and what they inherently desire.

That’s why leaders and economists need to understand the difference between the meaning of work (i.e., to earn a paycheck) and meaning in work (i.e., to experience mattering, worth, and dignity).

If we’ve learned anything from the aftershocks from each of the major financial disasters and work revolutions, it’s that a job won’t cure despair if the person experiences despair in the job.

Many politicians and economists obsess about the quantity of jobs, but organizational leaders should focus on ensuring the quality of those jobs.

Decades of studies now show that experiencing work as positive, purposeful, and significant is a predictor of positive outcomes like motivation, engagement, and overall well-being in life.

Oxford University professor Ruth Yeoman writes that meaningful work must be recognized as a fundamental human need because it satisfies the inescapable human interests of dignity, freedom, and autonomy.

When those interests are not met, either because of unemployment or by a degrading job, a sense of hopelessness, desperation, and meaninglessness can ensue, especially in already vulnerable populations.

How to Make Work More Meaningful

A recent study by Mckinsey & Company found that over 55% of what contributes to employee well-being and engagement come from non-financial or job security factors.

The most significant factors in enhancing overall well-being are individual purpose and contribution, social cohesion and inclusion, and trusting relationships. These elements serve as the basis for creating environments that facilitate meaningfulness.

Here are some ways to enable meaningful work:

1. Cultivate a Culture of Mattering

Experiencing significance is found to be a key predictor in overall mental health. Psychologists Morris Rosenberg and Claire McCullough, in a classic study, find that mattering manifests when someone feels noticed, important, and needed.

While mattering seems like common sense, it’s not common practice. The Gallup Organization finds that upwards of 65% of people don’t feel appreciated at work.

Some actions to cultivate mattering include:

- Authentically check in on the people you see and talk to every day.

- Learn about people’s personal lives and remember those details and ask about them regularly. Encourage employees to do the same for each other.

- Learn how to foster psychological safety to demonstrate that people’s contributions are valued and needed.

- Continue to invest in personal development and well-being in all positions equally.

- Remind people regularly how their unique strengths are integral to delivering a bigger purpose. Show people how they’re indispensable.

2. Redesign Jobs and Tasks for Meaningfulness

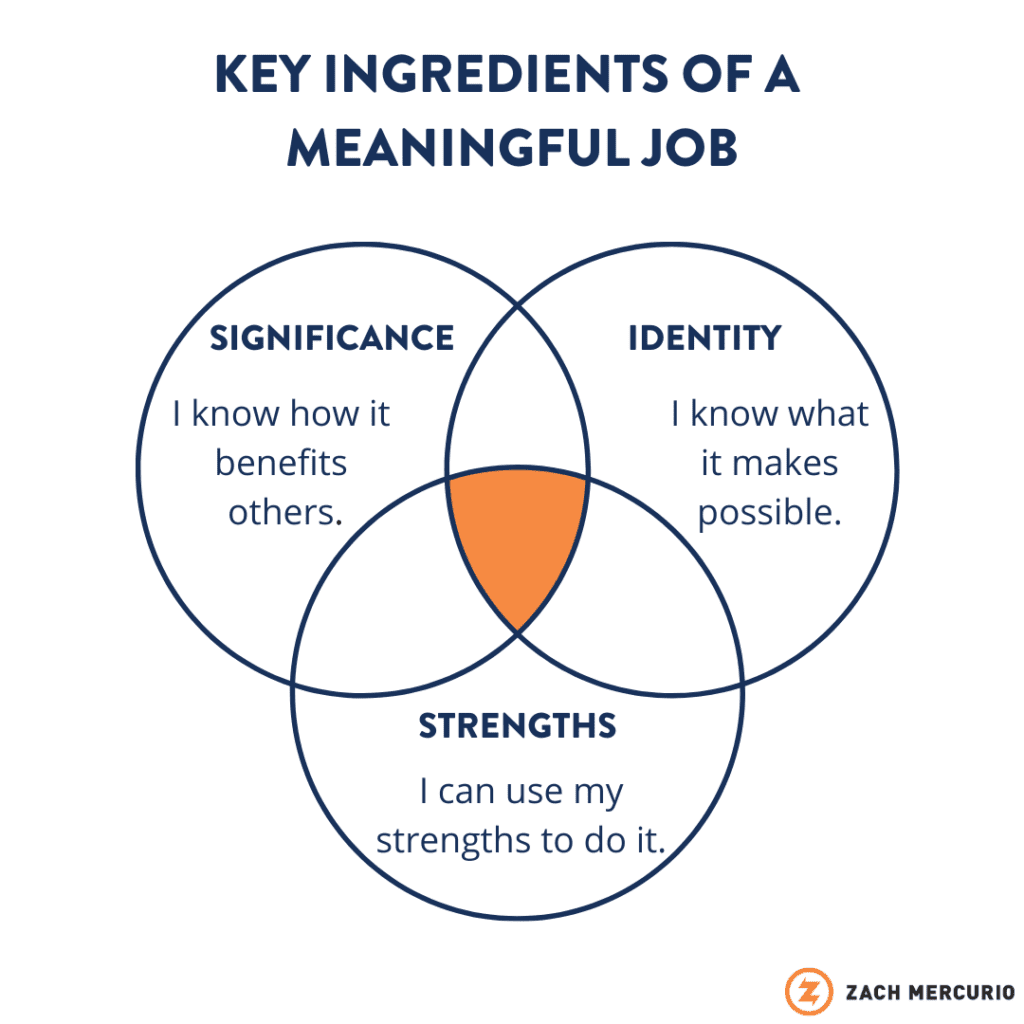

In 1975, organizational psychologists J. Richard Hackman and Greg R. Oldham studied 658 workers in 62 different jobs. They found workers need to be able to do and experience three elements in a job or task to experience meaningfulness.

First, they must know the significance of the task to another person. Second, they must be able to identify how the task fits into a bigger outcome, and third, they need to be able to see how they can use their pre-existing strengths to accomplish it.

This model holds up in the research today and reaffirms that leaders can enable meaningfulness in any job.

Some actions to redesign jobs for meaningfulness:

- Through recruitment, training, and onboarding, ensure that tasks and jobs are introduced by first showing why the work matters, what the job makes possible, and how the individual’s strengths are critical to doing the job.

- Regularly collect and tell stories of the work’s impact on others. Bring in the beneficiaries of the work to tell the story of how the work impacted their lives.

- Give regular, purposeful affirmation that directly shows people how their work on a specific task made a difference for you or others.

- Give employees autonomy to adjust how they can best do their jobs using their strengths. Invite people to provide feedback on their work and become an expert.

3. Ensure dedicated time and space to building meaning-giving relationships.

Our research on front-line workers finds that positive relationships maintain meaningfulness.

Meaning-giving relationships can reaffirm mattering, facilitate a sense of belonging, and can facilitate growth and development.

University of Michigan researchers Jane Dutton and Emily Heaphy find that these high-quality relationships are characterized when both people in the relationship are known and cared for, gain positive energy from interactions, and experience an equal investment in the relationship.

Creating space for all people in all positions to form these high-quality connections, in-person or virtually, is vital for sustaining meaningfulness.

Some actions to facilitate meaning-giving relationships:

- Create peer coaching and mentoring networks and invest in personal and professional development for people to cultivate mattering and inclusion for those around them.

- Incentivize peer recognition. One of my favorite platforms is Bonusly, a digital platform that encourages affirmation of other’s contributions.

- Intentionally create the time and space for authentic, informal, meaningful relationships to occur, especially on virtual teams.

- Allow autonomy for people to choose who they work on projects with, incentivize collaboration, and work on teams.

Enabling Meaningfulness is a Leadership Skill

Most organizational leaders never formally learn how to cultivate mattering, instill meaningfulness, and promote meaning-giving relationships.

Enabling meaningful work is a skill that I believe will be the next century’s vital leadership competency.

People’s lives may depend on it.