Last month, the U.S. Surgeon General named “mattering at work” a top priority for improving mental health. The announcement reaffirms what we’ve known for many years: Mattering and well-being are inseparable, especially where humans spend 35% of their waking lives.

The official call to prioritize mattering at work is the culmination of several conspiring forces reshaping what work means to and in our lives.

Survey research shows that the pandemic prompted people to reflect more on the quality of their jobs and their lives. Data from the past two years indicate that people left their jobs not for more pay, benefits, or flexibility but largely because of disrespectful cultures, non-inclusive climates, and uncaring leaders.

People deemed “essential” workers are now asking, “Do I feel essential?” We’re experiencing compounding health and job insecurity. The unemployed are returning to work, with studies showing that feelings of worthlessness constitute a major risk factor for those transitioning from joblessness. Feelings of being forgotten and loneliness are at all-time highs amidst rising calls for social justice and inclusion.

Upheaval events amplify people’s search for meaning, and we’re seeing a grasp for significance and demand for dignity in work. Creating mattering is a necessary answer.

What is Mattering?

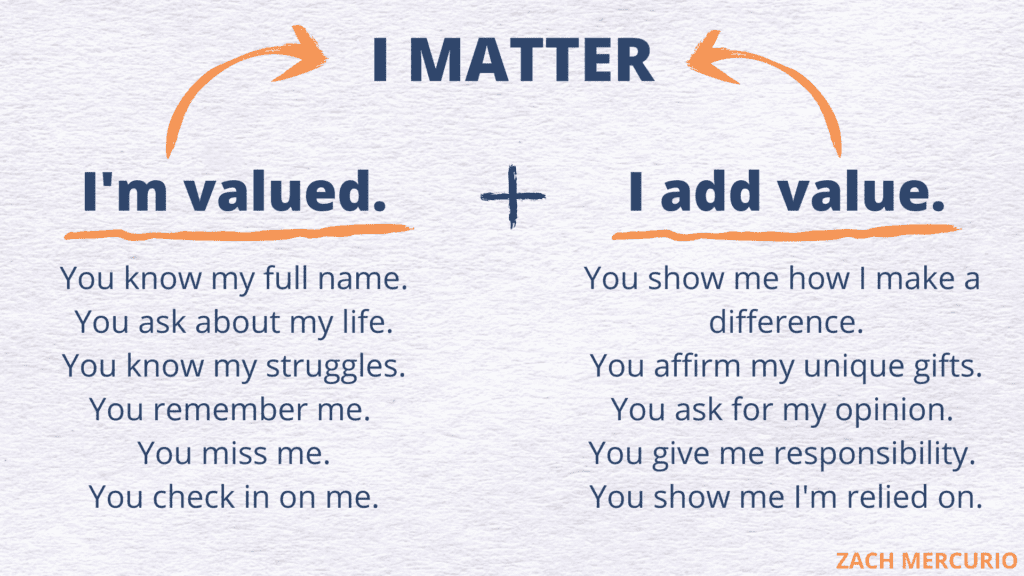

Mattering is the belief that we’re significant to the world around us. Psychologists and sociologists find that mattering arises from two primary experiences: 1. Feeling valued by those around us, and 2. Adding value to those around us.

Mattering isn’t the same as self-esteem. Self-esteem is confidence in our worth and abilities. Self-esteem is one internal outcome of experiencing mattering to others. Mattering isn’t interchangeable with “belonging” either. When we feel like we belong, we feel welcomed, accepted, and approved by a group. When we feel like we matter, we feel significant to members of that group — we feel seen, important, and needed through how others treat us. A sense of belonging increases the chance we experience mattering and vice versa.

When people do feel valued and know how they add value in life and work, decades of studies show they’re less likely to experience unhealthy stress, anxiety, and severe depression and much more likely to experience increased self-esteem, motivation, and overall well-being.

In contrast, the perpetual belief that one doesn’t, can’t, and won’t matter is a hallmark of low self-esteem, disengagement in life and work, withdrawal, and clinical depression. One study of 1,026 Tennessee residents found that feeling insignificant predicted objective stress indicators like higher cortisol levels and blood pressure.

It’s easy for nothing to matter to someone who doesn’t believe they matter.

The Mattering Instinct

The need to create mattering at work is not a new well-being trend or “touchy-feely” idea. Creating mattering is about as “touchy-feely” as feeding someone who’s hungry. When we create mattering for others, we meet a basic human need and fulfill a primal survival instinct.

Mattering comes first. When we’re born, our survival depends on whether we matter to others. As a newborn, one of your first reflexes was to lift your head and scan the room to search for someone to care for you. You then reached out to grasp that caretaker. We need the care of others, and our primal need for attachment doesn’t go away as we move into and through adulthood.

The survival instinct for attachment grows into the social need to be noticed and included by others. Psychologists Roy Baumeister and Mark Leary labeled the desire for caring interpersonal relationships a “fundamental human motivation.”

New York University philosopher and Humanities Medal recipient Rebecca Newberger Goldstein goes further and deems mattering a core instinct that drives all human behavior, saying, “Our mattering instinct is inseparable from pursuing a coherent human life.”

Mattering is an animating force of life.

That’s why, when someone doesn’t believe they matter at work, it’s easy for nothing to matter. People won’t share their voice if they don’t believe their voice is significant. People won’t use their strengths if they don’t believe they have strengths. People won’t contribute if they don’t believe they have something to contribute. People won’t care until they feel cared for.

Mattering comes first and filling people’s need for significance must be a core practice for redeeming work and revitalizing our organizations and society.

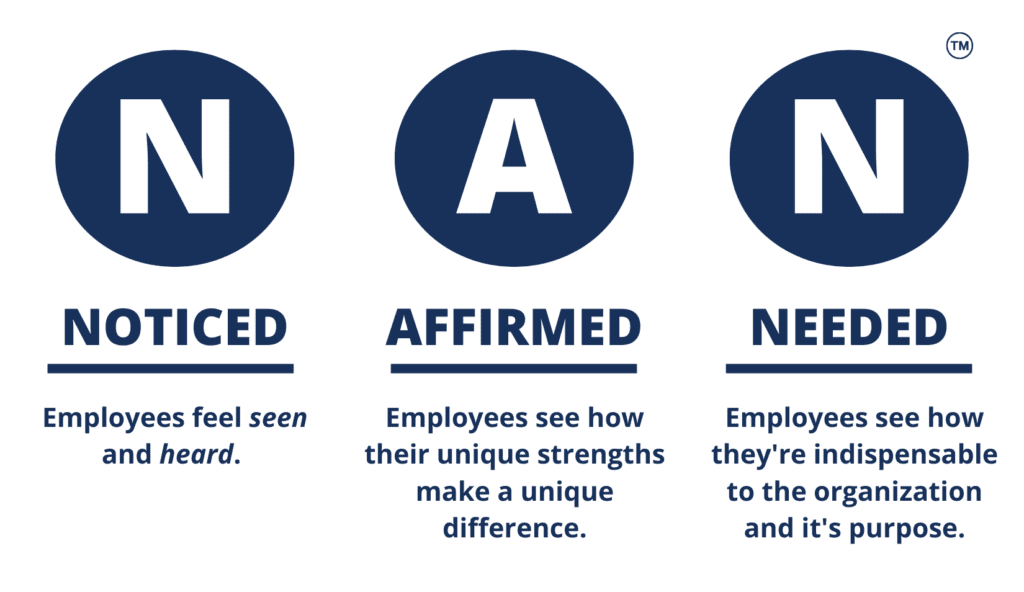

The three primary drivers of mattering at work are: 1. Feeling Noticed, 2. Feeling Affirmed, and 3. Feeling Needed.

Noticing

Noticing others is the deliberate act of seeing someone’s uniqueness, paying attention to the ebbs and flows of their lives, and taking action to show them you see and hear them.

Noticing someone isn’t the same as “knowing” someone. You can know your best friend but not notice that they’re struggling. You can know a team member but not notice that their parent is in the hospital or that they’ve been struggling with a project.

Feeling seen is necessary for mattering, yet it’s often overlooked. Global surveys find close to 43% of employees feel “invisible.” When it comes to taking an interest in others, it seems common sense isn’t common practice.

Here are several practices and skills to ensure people feel noticed:

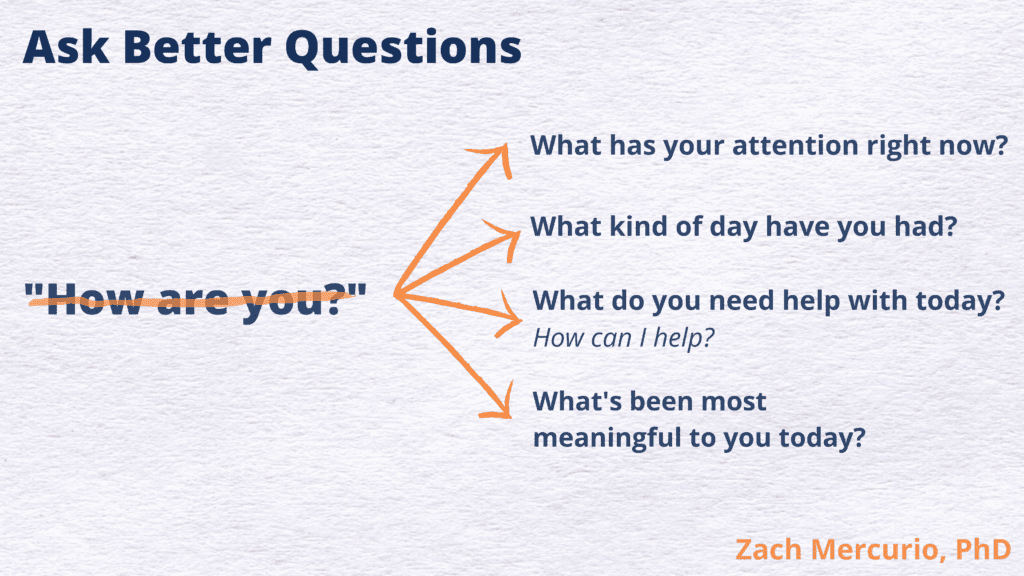

- Do regular check-ins with employees that focus on their personal lives, stress levels, and work struggles. Simply changing questions from “How are you?” to questions like, “What has your attention right now?” or “What do you need help with? How can I help?” can give you more insight into people’s lives.

- Note critical events and news in people’s personal lives and schedule time to check in. Remember people’s full names or find out how your employee who was sick a couple of weeks ago is doing.

- Create space for people to share how they’re doing before you discuss what they’re doing. One researched practice is implementing a green, yellow, or red check-in to assess people’s stress levels. Green means you’re feeling in flow and have low stress. Yellow means you’re feeling stressed, and red means you’re overloaded. Studies show that awareness of others’ moods can create a culture of empathy and compassion.

- Practice compassion. When you notice an employee struggling, offer an immediate action to help. Compassion is empathy in action. Spend some time thinking about employee needs or struggles. What can you contribute to help? For example, if you hear an employee say they’re feeling burned out and overloaded at the beginning of a meeting, offer them the opportunity to miss the next meeting to get caught up. Small acts of compassion go a long way to creating mattering.

- Tell people why you missed them if they were gone. When you show someone the significance of their absence, you’re showing them the significance of their presence.

- Make sure people can share their feedback, ideas, or mistakes without fear of retaliation by committing to a climate of psychological safety.

Affirming

Real affirmation is showing people how their unique strengths make a unique impact. In workplaces, meaningful gratitude and affirmation are infrequent, and most workers report feeling perpetually underappreciated and undervalued.

Affirmation is more than an awards ceremony, simple acknowledgment, or a pay raise. Real affirmation is creating an environment that regularly provides people the evidence of their significance.

Here are some essential practices to affirm others:

- Collect and tell stories of people’s impact on others. Ensure that people can regularly see, hear, and feel their work’s upstream effect on teammates, leaders, and end beneficiaries.

- Instead of just saying “thank you” or “good job,” show people the difference they made or how they made it. A simple way to start is by giving what I call Purposeful Affirmation. First, remind the person of the specific situation in which they made a difference for you. Next, name the unique strengths they used and their particular behaviors. Finally, and most importantly, show them their impact on you or someone else.

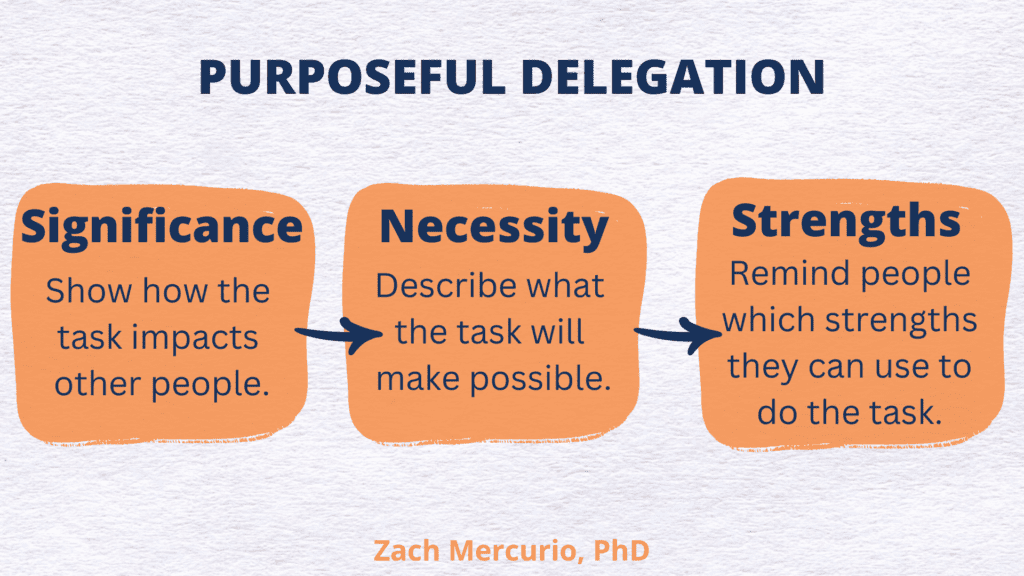

- Make sure that before you tell someone what to do or how to do it, you show them why it matters. There are three researched qualities of a meaningful task. First, people should experience how the job benefits others (Significance). Second, people should be able to describe how the task is necessary for a bigger outcome or project (Necessity). Finally, people should know how to use their unique strengths to do the job (Strengths).

- Ensure you can name each employee’s differentiating strengths and that each person has an individualized development pathway to build on and develop those gifts.

Show People How They’re Needed

Human beings are at their best when they’re needed. In our research, when we ask people to describe moments mattering in their lives, people often talk about becoming a caretaker, a parent, or being called on to assume responsibility for someone else. It’s no different in work; when people feel irreplaceable, they act irreplaceable. They show up. They commit.

On the flip side, when people feel replaceable, they act replaceable. They won’t show up. They won’t commit. Ensuring people feel indispensable and needed is key to creating mattering.

Here’s how to show people how they’re needed:

- Make sure people see how indispensable they are to delivering a bigger purpose. Famously, when John F. Kennedy was about to give a speech to launch the Apollo mission, he asked a space center janitor, “What do you do here?” The janitor replied, “Putting a person on the moon.” Wharton School researcher Andrew Carton found that one way NASA made people feel indispensable to that big purpose was through a “ladder to the moon,” which leaders scrawled on blackboards in NASA facilities. At the bottom of the ladder were the group’s tasks. The next rung was a tangible, measurable objective that the tasks made possible. The next rung was the concrete, quantifiable goal that the former objective made possible, and so on until the top rung: “To put a person on the moon by the end of the decade to advance science.” People vividly saw how their work was indispensable.

- “If it wasn’t for you….” are some of the most powerful we can say to one another. Say, “if it wasn’t for you…” to people regularly. One leader I worked with at a large bank told me that on Fridays, she messages a person who helped her get through the week and writes, “If it weren’t for you, I wouldn’t have made it through the week,” and then describes why.

Try it right now. Think about the people you need. Take a moment today to tell them, “if it wasn’t for you…” and then watch what happens.

You’ll see and experience what the research indicates: Few things are more powerful than when a human being realizes they matter.