A couple of years ago, a supervisor asked me to work with a group of supposedly “unmotivated” maintenance workers.

One of their daily summer responsibilities was washing the buildings’ bottom floor windows in a large complex. I interviewed each employee and asked, “If you were running this place, what would you do differently?”

These were not “unmotivated” workers but wise people with opinions on how to make their work better. I felt the energy. I barely had enough time to listen to all their ideas. After an interview, one of the workers pulled me aside and asked if we could talk.

What she told me next explained the “motivation” issues on the team.

Her supervisors tasked her with the daily cleaning of the bottom floor windows of the complex. She came in, did the task, and then finished her day. After about a week, she noticed a confusing pattern. Every afternoon at 3 o’clock, the sprinkler system turned on.

She observed that the sprinklers were all aimed to splash every window. Dried water splotches quickly appeared. Each subsequent morning, she began by cleaning an avoidable mess. She soon realized that this was why the windows had to be washed daily.

Excited about the discovery, she asked to meet with her supervisor. She explained that if they could readjust the sprinklers’ aim, they could save much worker time and energy. She eagerly awaited praise for her time-saving idea. But her supervisor responded, “That’s the sprinkler people’s problem. That’s not our problem. I need you to do your job.”

She was dejected, shut down, and silenced in a few seconds. She shared her voice and idea but was told to “do your job.”

That was five years ago.

Anti-Mattering

When we share our voice, we share part of ourselves. When our voice is unheard, we become unheard. That worker later told me, “…in this job I feel pointless. Why do I bother?” So, she “put her head down” and just did her job and nothing more.

Was she “unmotivated?” No. She experienced what psychologist Gordon Flett termed “anti-mattering” — feeling insignificant to those around us. Anti-mattering is the inverse of mattering. Dig deep enough, and you’ll find that many “motivation” or “people” issues in our organizations and society are anti-mattering issues.

To someone who doesn’t feel like they matter, it’s easy for nothing to matter.

Anti-mattering destroys energy, undercuts self-worth, reduces self-esteem, and can predict unhealthy stress, clinical anxiety, and depression. Feeling unimportant also contributes to chronically low engagement, commitment, and performance. In workplaces, data show that close to 30% of workers feel invisible at work, 27% feel ignored, and almost half feel undervalued.

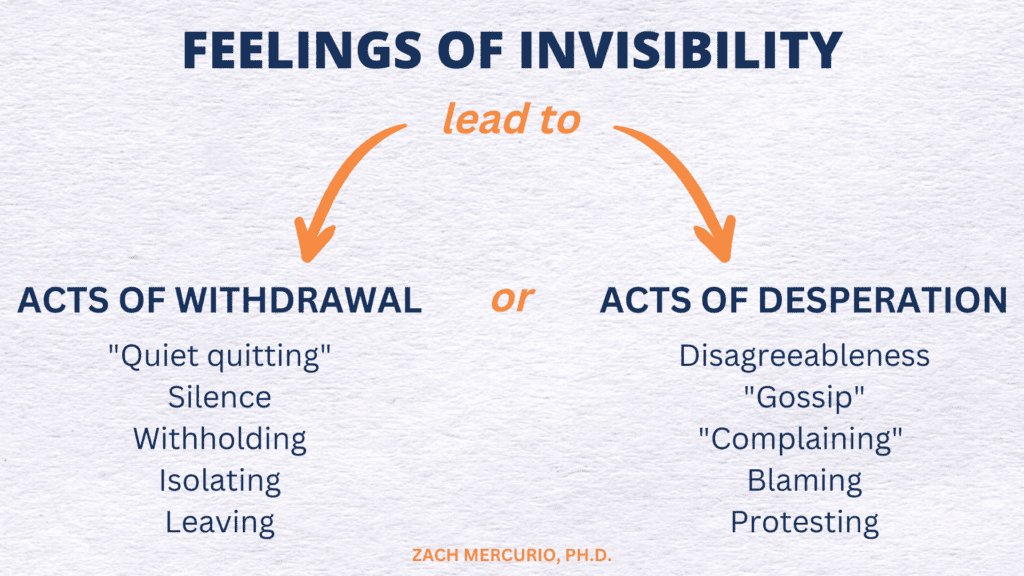

Feelings of not mattering result in acts of withdrawal or acts of desperation.

Acts of Withdrawal

In March 2022, a career coach and influencer asked his TikTok followers, “Do you have a job you don’t want to quit?” Then, he recommended, “Try being lazy instead. Many people are just kicking back and taking it easy instead of quitting their jobs, and it’s working.”

The “quiet quitting” trend was born. Around the same time, in China, a user on the social media site Baidu wrote, “Lying Flat Is Justice,” spurring the viral “lying flat” movement. The “lying flat” movement is a collective renunciation of work or effort by overworked, stressed younger workers who feel undervalued and unsupported by society.

The fact that these terms went viral is not evidence of a lazy, entitled generation. Instead, their virality is evidence of the ubiquity of anti-mattering in modern work and society.

Acts of withdrawal are survival and coping mechanisms and are the inevitable byproducts of feeling insignificant. Silence, withholding, and isolating are other common withdrawal behaviors.

The eventual and terminal withdrawal behavior is leaving, commonly labeled in organizations as “turnover.”

Acts of Desperation

When feelings of anti-mattering become consistent and persistent, people often act out in desperation.

Desperation is a state of despair that results in extreme behavior.

Disagreeableness, gossip, complaining, blaming, and protesting are often frantic attempts at getting attention and securing significance. In my practice, I find that many employees whom leaders have labeled “difficult employees” are usually the most unseen, unheard, and under-recognized employees.

Take “gossip,” for example. Research shows the two most prominent predictors of negative gossip are what’s known as “psychological contract violation” and abusive supervision. A “psychological contract” is the unwritten, informal expectations of support and fair treatment that exist between an employer and their leader or an organization.

Abusive supervision is characterized by disrespecting, controlling, undervaluing, and manipulating. Surveys show that outright abusive management affects nearly 13% of workers, and almost 84% of people indicate they’ve worked for a boss who exhibits uncivil and degrading behavior.

When people can’t speak up to a leader, they’ll eventually speak out to one another.

Gossip and complaining are usually symptoms of a silencing culture or leader, not simply a “bad employee.”

Decades of studies in psychology show that the most common predictors of attention-seeking behaviors are the unmet emotional needs of validation, support, and positive reinforcement and the resultant low self-esteem.

But we often mislabel these attention-seeking behaviors as “people problems.”

Nearly every “people problem” is a cultural and systems problem. In many of these cases, the actual underlying problem is systemic anti-mattering.

When people feel unseen and unheard, they typically resign themselves to helplessness or act out to secure a sense of significance they don’t experience.

The Answer

According to Flett, the term anti-mattering pays homage to the physicist Paul Dirac, who developed the modern theory of antimatter. In physics, “antimatter” is ordinary matter with an opposite electric charge.

People get a powerful charge from experiences of mattering and the same equally powerful, yet harmful, charge from experiences of anti-mattering.

It’s tempting to think the maintenance worker’s supervisor was just a lousy boss. But all our teams, organizations, and communities have “sprinkler issues” — small, banal moments that cause people to feel unseen, unheard, and unvalued.

To counteract experiences of anti-mattering, we must root out these insidious moments and consciously work to create experiences of mattering and ensure those around us feel noticed, affirmed, and needed.

This article contains excerpts from Zach’s forthcoming book on the power of mattering.

Zach Mercurio, Ph.D., is a purposeful leadership, mattering, meaningful work, and positive organizations researcher, speaker, and author of “The Invisible Leader: Transform Your Life, Work, and Organization with the Power of Authentic Purpose.”